Rural Reverb'

A weekly column in Redheaded Blackbelt

#7 Weed Fatigue and a Historic Event

By Scott Holmquist

Views in this dispatch are those of the writer, not the Humboldt Area Peoples Archive.

Way back in the 2000s I complained informally to a top Humboldt Historical Society officer, someone I liked and knew personally, about the Society’s failure to offer much of anything after 1960. Why nothing on the massive invasion of hippies in the 1970s, for instance?

Way back in the 2000s I complained informally to a top Humboldt Historical Society officer, someone I liked and knew personally, about the Society’s failure to offer much of anything after 1960. Why nothing on the massive invasion of hippies in the 1970s, for instance?

He sympathized. He agreed. And then he said the Society needed desperately to raise money to repair its roof. It needed new members and sponsors. It needed to process dozens of boxes of material. How was it supposed to deal with another half-century?

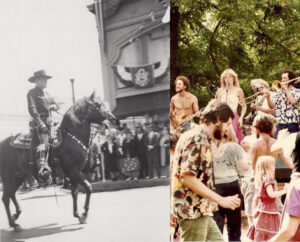

In that missing half-century, Sixties Counterculture in the form of enviro and other community activism, theater and art, back-to-the-land settlement, alternative businesses and the cannabis economy reshaped Humboldt County.

If these histories are absent from mainstream local institutions, anti-hippie bigotry is not to blame. The people who made local counterculture-related history have not done what it takes to assure its preservation and promotion. So far, there is no hippie, dope grower, or enviro equivalent to the Eureka High School teacher, Cecile Clarke, who sold her family’s sheep farm in 1960 to finance the Clarke Historical Museum.

If you see a lot about logging history at the Humboldt Historical Society, it’s because loggers and logging enterprises have provided the photos and support.

This week, HAPA, a group I formed with retired Cal-Poly archivist Edie Butler and Southern Humboldt community leader Douglas Fir, will host a discussion and performance in Arcata to make the case for not forgetting this missing half-century and its impact.

As far as I can tell, our modest event, not at the university or any institution, but at a fermented-fruit beverage joint, will make history.

For the first time an organization dedicated to preserving local history will invite the public to consider how Sixties Counterculture transformed the Humboldt region, bringing together scholars from a major university and people who made, and are still making, some of that history.

Why bother?

Since the 1970s, the people and ideas that emerged from Sixties Counterculture have changed the politics, the culture and the economy of the Humboldt region more any single historical force.

A short incomplete list:

The North Coast Co-op (1972), Eureka Natural Foods (mid-1980s) and Wildberries Market (1994), are hippie inventions or spinoffs. The Open Door Clinics and Redwoods Rural Health Center, were hippie initiatives, so was the credit union now called Vocality, originally the Mateel Community Credit Union.

The Southern Humboldt hippie homesteader David Katz established one of the first national solar power retailing businesses, Alternative Energy Engineering (AEE), becoming a major local employer, seeding other hippie businesses that engineered and locally manufactured off-grid power technologies. Homesteading hippies Leib Ostrow and Linda Dillon founded what became the largest national producer and distributor of music for children, Music for Little People.

The the story of local LGBTQ+ liberation, in its current form, is rooted in Sixties activism and sexual openness. There was a lesbian back-to-the-land “neighborhood” in the Southern Humboldt hills in the 1970s. Recently deceased Eureka activist and artist Richard Evans found community as black gay man first among Bay Area hippies, then among their homesteading brothers and sisters in Southern Humboldt in the 1970s.

Today, thousands of acres of forest are protected thanks to hippie organizing, litigation and protest led by organizations like the Environmental Protection Information Center (EPIC), founded by radical Southern Humboldt activists in late 1970s, and its sister org, the North Coast Environmental Center founded in Arcata in 1971.

Then there’s cannabis. The counterculture blessing and curse that put Humboldt on the world map in the 1970s and kept it there for decades.

Archiving v. Action & Weed-fatigue Syndrome

The Sixties Counterculture people most capable of building institutions and businesses have always been more concerned with saving the planet and their fellow human beings, or developing products that may do the same, than stacking and sorting the records of their history.

When I tried to convince a forest activist in the Petrolia area that saving records of his work was important, he huffed, “So, how many trees will that save?!”

Another more complicated factor which has impeded local history is weed-fatigue syndrome.

Many women and men who built and maintained local hippie institutions and businesses that had protected and benefited from the cannabis economy eventually regretted their success. There was even shame associated with it. For decades, among the hippie elite, one could not be, “Just a grower.”

Shame and regrets associated with weed, among other divisions, crippled what had evolved to be an often fiercely united network of communities in Southern Humboldt. Their failure to coalesce around a strategy to prepare for legalization is one consequence of this weed-fatigue. Another is the reluctance among those best positioned to record and preserve the region’s history, because to tell the story in full, weed’s shameful prominence is unavoidable.

Humboldt Historians

I’ll guess weed-fatigue likewise could explain why among the writers featured at a recent fundraiser at the Clarke Historical Museum, “Meet the Humboldt Historians!,” none has written explicitly about Humboldt’s counterculture since their lineup’s star, Ray Raphael, cranked out his 1984 chronicle, Cash Crop.

Raphael’s latest book, I Like It Here: Life Stories of Humboldt’s Bob McKee, as told to Ray Raphael (2022), indirectly about local counterculture, is a tour-de-force oral history of the ‘Godfather’ of Southern Humboldt hippie homesteaders, the man singularly responsible for the high concentration of counterculturists in the region. But in what appears to be another case of weed-fatigue, the book completely elides the cannabis economy’s importance to McKee’s life story. From this book you will not know illegal cannabis grown by the people McKee set up in the hills was, from the start, the engine of the local economy that kept chugging for two generations. You won’t even know there was a weed economy.

To write local histories of Sixties Counterculture impacts, for good and ill, we need evidence and people who understand its value. The historic discussion and performance in Arcata this week will may help.